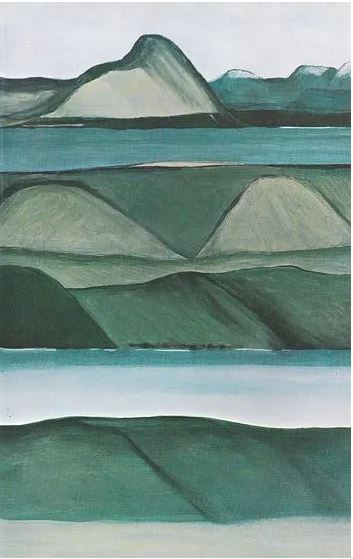

Three Otago Landscapes by Colin McCahon

Written By:

David Trubridge

Three Otago Landscapes by Colin McCahon

In a beautiful piece for New Zealand Geographic, Kennedy Warne writes about his feeling for the land, how one day he was surprised to find tears welling up in his eyes as he sat by Lake Taupo. He noted how when he first started up the magazine it was as a factual scientific journal. But over the following 30 years things have changed in our attitude to the land. In New Zealand, some of this can be attributed to a growing sensitivity to Māori values, but also to the dawning realisation that the western “transactional” attitude to the land is becoming a catastrophic disaster. Kennedy cites a quote by Colin McCahon written about one of his Northland paintings, “A landscape with too few lovers”, which could refer to either cause.

Reading this was for me one of those ‘ping’ moments of recognition when you discover someone else voicing thoughts you are also having. I have recently found myself undergoing similar feelings of emotion towards the land. And I wonder where it comes from: is this some kind of common zeitgeist that our culture is going through? Or is it more personal, a manifestation of changing emotions as I age? Most likely, both things are happening.

The general zeitgeist case is well written about. Western values emanating out of Europe, particularly Britain, have placed man (I use that word advisedly) at the centre and pinnacle of evolution. It was the right, even god-given duty, of man to exploit the land. “Lazy” natives who had lived in balance with the land for countless generations were seen to have abrogated that duty and hence had no right over the land. So we elbowed them aside and ripped out the forests, spread the farmlands and dug up the earth. And now we realise that we have gone too far, but such is our inertia and such is the power of invested business interests, that we carry on regardless. We mourn the loss of wildlife and argue about the threat of climate change, but will not change our lifestyle. Some people do care and are now looking at alternative world views, like Te Ao Māori, that see humans as merely one integrated part of life. We need more lovers, those who love the land more than they love their possessions and status.

But what about the personal case? Is there a common trajectory of changing ideals over our lifespan? In our youth, with all our lives ahead of us, we are driven by ambition and idealism: anything is possible. I remember one of the texts that most summed up my feelings at the time:

“What joy to climb the mountain’s holy solitude

alone in its clear air, a bay leaf in your teeth,

to hear the blood pound in your veins up from your heels . .

never to say, ‘I’ll go to the right,’ ‘I’ll go to the left,’ ”

(From ‘The Odyssey A Modern Sequel’ by Nikos Kazanzakis)

In the privileged world of opportunity in which we were brought up, goals were self-orientated. You went out there and made your life, and whatever you did not achieve today you could always do tomorrow. The tingling sense of potential was a powerful driving force. I had the sense that, as a creative person, everything matters — all the things I do and all the experiences I have will inevitably, at some point in the future, lead to something more. My relevance in the world came from the things that I made and the ideas that I expressed.

But this feeling of potential must change as your allotted lifespan ahead starts to shrink. Now in my late 60s I find myself going through a major shift as a sense of finality grows more urgent. No longer can I be confident that today’s experiences will be the seed of future developments or achievements. Time is running out. I look back on my life and realise that this could be all of it. This means that I have to think differently about those experiences — that I now have to consider them as ends in themselves because there might be no tomorrow. Everything I have based my life on is turned upside down. To understand this more, I went looking.

It is revealing that Māori, and many other indigenous cultures, have a very different view of time to Westerners. They face ‘backwards’, or to be more accurate, in the opposite direction. I have lived my life facing forward, thinking about the future, but Māori feel that it is pointless to look forwards when it is into the unknown. They prefer to focus on those who have gone before and to let that knowledge and example be a guide. This could be a way of greater wisdom where there is less chance of repeating past errors.

An emphasis on ‘living in the now’ suggests Mindfulness which has recently become a popular discipline. It is not new, probably first reaching greater awareness through the writing of Eckhart Tolle in the early 90s. But mindfulness is seen more as a psychological treatment for an over-stressful life, a necessary defence against the demands of society today, than as an end in itself. Unlike the Māori ancestral view, it shuts out all thoughts of both past and future, to focus on the now.

More appropriate for me is Zazen, the Japanese Buddhist discipline of just sitting still, focusing on body and breath while excluding any thoughts or judgements. Through Zazen I discovered Ikigai, also from Japan. In a lovely little book of the same name, Mari Fujimoto describes Ikigai, “or something to live for, (as) the kernel of enjoyment and motivation that gets us up each morning.” It will allow you to “come to an understanding of what is rewarding and worth focusing on . . . as opposed to those forces that are distracting”. Mari’s book describes about 40 other Japanese words that have no direct English translation simply because those subtle concepts and relationships are alien to our culture.

I have always loved walking in the mountains and wilderness. When I was younger the experience was more of an affirmation of self, but more recently it has become an opportunity purely to experience empathy with nature. No longer do I need to get to the top of the mountain or to the end of the trail — now it is enough to simply be there. I love the immersion that the rhythm of walking gives, but I also love to just stop and sit. This is a metaphor for life: my Ikigai is not related to the “distracting forces” of what others think now or in the future, but in what I am experiencing this moment.

This has a very important implication for all of us: if we stopped to appreciate what we have now all around us in nature we might come to value it more, to understand our inseparable connection to all of life, rather than to be driven by our self importance and hubris. This shift would place our world view closer to that of indigenous societies, and it would offer greater optimism for our future. So I hope the shift is not just a function of personal ageing, but is also a maturing of Western society in general, away from a dependence on rapacious development.

And yet . . . as I sit there on a mountain or by the sea, and I feel that welling of emotion that Kennedy described, there is still the artist part of me that wants to convey the beauty of the moment, just to say to everyone, “Look!” . . .